A Different World: Bears Belly

Much had changed over the centuries since life sprung from Mother’s womb to when Bears Belly sprung from his mother’s womb. People were divided and largely disrespected life. Nearly everyone was fighting one another. The living beings had begun to take the path of Sickness and Death in their rebellion against life. Yet, life is what was given to Bears Belly when he emerged from his mother’s womb, he took his first breath and screamed his first prayer into a seemingly unforgiving world. Bears Belly’s name written in Arikara is Ku’nuh Kana’nu, and he would live up to that name and his ancestry by creating a path more in line with his Creator Neshanu’s way than Death’s way.

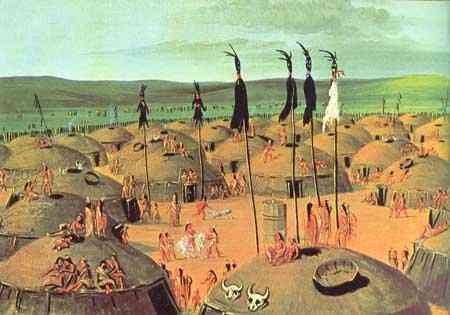

Bears Belly was born in 1847 at Fort Clark, North Dakota. The remnants of the fort are available to visit today only as ravaged remains and archeological sites. Fort Clark had a troubled existence and a difficult history, leading to its abandonment only a decade after Bears Belly was born. The Mandan occupied the area in the early 1800s when fur traders built and established the fort nearby to create a trading post south of the Mandan village. Since the traders were positioned on a bend in the upper Missouri River, they had a prime location to sell and transport their goods to any of the U.S. territories. The site was also a prime location for tourists, trappers, adventurers, and others to visit and bring their talents, wares, and diseases to rural Indian country. The Mandan settled in the area in 1822, and it quickly became a trade hub. The initial Mandan village consisted of earth lodges, houses made with soil from the ground covering a simple frame of cedar logs inside and forming different sizes to meet various needs, from family dwellings to community meeting places. The soil provided insulation for the harsh winters and humid summers of the northern plains, making the earth lodges highly efficient and desirable homes, much better than the portable canvas tipis they used to roam.

The Mandan were mainly agricultural-focused, choosing to grow their food instead of gathering it. There were farms spread about the area nurturing corn, beans, squash, pumpkin, and tobacco. The Mandan often spent the Spring, Summer, and Fall in this village and then migrated to the woodlands around the Missouri River to spend the winters there, enveloped by the protection of Mother Earth’s trees. On the prairie, with few natural barriers to cut the wind and migration of snow when it came in abundance, winters proved dangerous as life struggled to survive the frozen onslaught. Little did the Mandan know that an alien onslaught was headed their way.

Fort Clark originated around 1830 as James Kipp, an employee of the robust and profitable American Fur Company, saw the potential for trade with the Mandan in the area and noted their proximity to an easily traversed waterway that would deliver their goods to settlements across the country. Kipp initiated the building of the fort, a 19,200 square-foot plot of land surrounded by fortifications and taking up a little less than half an acre of land near the already existing Mandan village. Inside the fort, a house was built to be the main quarters of the head trader, which wasn't Kipp, and a few other buildings were designated for processing and storing the pelts they obtained through the fur trade with the Mandan. An invitation was sent out once this fort was built, and visitors started floating into the area.

Famous steamboats such as Yellowstone and St. Peters bought and shipped goods from the area. Valuable hides like beaver pelts and bison skins, along with relics of Indian life such as pipes and tobacco, were shipped out while far-away delicacies, goods, and liquor were shipped into the fort. Even historically significant people like George Catlin, an explorer and chronicler of the plains Indians, boarded the steamboats into Indian country to document what he could about the Indians and share his research with a public that was altogether curious about what was happening in a world far enough away yet dangerous enough to bear worry and consideration.

A smallpox epidemic swept through the land in 1837 and wiped out the Mandan living in the area only ten years before Bears Belly was born in the same location. A majority of Indians confined to the area around the fort, and who had been there long before the fort existed, died due to the illness brought by the visitors floating up the river. Their immune systems were unprepared for the onslaught of novel germs that invaded their bodies. This disease sparked an epidemic that ravaged the northern plains for five years, continuing its assault against Indian bodies, tearing men, women, and children asunder due to its brutal nature. Large numbers of Indigenous people died during this epidemic, numbering into the thousands and shrinking the tribes in the area to minuscule numbers. The Lakota Sioux, living south of the Mandan, described in their Winter Counts calendars of 1837 and 1838 the devastation of the illness. These Lakota calendars contained pictograph descriptions of notable events through the years and were used in addition to oral storytelling to convey history as the Lakota experienced it. These particular Winter Counts calendars mention the fact that an illness had claimed the lives of competing Native Nations throughout the northern plains. Some estimate that around 10,000 Mandan and other Indigenous peoples lived together as the disease broke out. Out of that number, 130 survived two years of a smallpox outbreak.

Others claim only a couple dozen Mandan survived the illness. These Indigenous bodies did not have any immunity against smallpox. European settlers had built an immunity over the years since the disease had ravaged their populations. The Indians did not have that same protection. Due to this outbreak, the Mandan abandoned their village at Fort Clark in August of 1838 and moved into the territory of the Hidatsa, who lived along the Knife River, for support. There were only a few Mandans left, and they needed help. The Hidatsa were there to help.

Before this outbreak began, another smallpox endemic occurred in the 1730s among Indians over what is now the Canadian border but also affected the Arikara, the tribe that Bears Belly was born into, reducing its numbers by thousands. Many researchers find it challenging to establish an exact number of dead. Still, the number cited often sits in the tens of thousands of those Arikara who lost their lives and dwindled their population to minuscule amounts. Smallpox again ravaged the Arikara, who was in the same area as the Mandan during the outbreak of 1837-8; however, due to the previous pandemic the Arikara faced, only 50% of those Arikara lost their lives during the 1837 outbreak that ravaged the Mandan. While the Mandan moved out of their village, the Arikara moved in, nestling right up to Fort Clark and its visitors. Another fort was built near the newly claimed Arikara village. Charles Primeau, a one-time employee of the American Fur Company, launched on his own and established Primeau's Post just north of the already existing and functioning Fort Clark and south of the now Arikara village, ensuring Primeau first access to the fur trade with the Arikara. Primeau sold his business to another firm in the late 1850s, which sold Primeau's Post to Fort Clark in 1860 after a portion of Fort Clark burned down.

Sickness and Death, meanwhile, kept their charge. Another outbreak hit the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara in 1851. This time, it was cholera that spread throughout the tribes. Then, in 1856, just a decade after Bears Belly was born and four years after a cholera outbreak in the same area, the Arikara faced another about with smallpox that further picked off their numbers. Fort Clark was beginning to look like a curse in itself. The Dakota attacked the fort constantly and, by extension, the Arikara who lived nearby. Eventually, both the fort and the Arikara decided to move out. After years of disease and war with the Sioux, the consensus among all men, no matter the language barrier, was to pack up camp and disperse.

Bears Belly and his family would leave a handful of years after the smallpox outbreak of 1851, alongside the rest of the Arikara beaten by Sickness and Death and the constant attacks of the Dakota who were taking advantage of the Arikara's low numbers. The Arikara moved near Fort Berthold to a place called Star Village. Fort Clark was entirely abandoned by 1862, serving only as firewood for the steamboats that moved along the river until all of the wood was gone.

Member discussion